Post: 1 October 2014

Earlier this week Heather Savory, chair of the Open Data User Group (ODUG), argued in a post that Ordnance Survey’s model for licensing of geographic data is a “fundamental barrier” to maximising the beneficial use of publicly owned data in Great Britain.

Ordnance Survey does publish some very useful open data products, but its most detailed and useful geographic data is still available only on commercial terms (with special arrangements for public sector organisations).

ODUG is calling on the Government to push OS to open up most of (or all) of its data, in order to promote competition and develop the wider information market. I very much support this call.

In fairness, Ordnance Survey has done a pretty good job promoting reuse of its existing open data since the launch in 2010. A preliminary economic study prepared in 2012 estimated the OS OpenData programme would generate net GDP growth of between £13.0m and £28.5m per year by 2016. A recent project to add open data to the popular Minecraft game has had favourable publicity and, more importantly, helped introduce open geographic data to a wider, younger audience.

OS OpenData is a success story – and it is time to build on that success. But Ordnance Survey is constrained by the trading fund model, which requires it to put revenue generation ahead of the wider interests of Britain’s information economy. As in 2010, moving forward will require political support at ministerial level.

National Information Infrastructure

ODUG and the Cabinet Office are currently drawing up a list of datasets that form the National Information Infrastructure. The first draft, released in October last year, was rather uneven – but the decision to include all of Ordnance Survey’s geographic data was both sensible and obvious. OS data is not only essential to the NII – it is in many respects the foundation.

One of the key concepts behind the NII is the idea that the utility of public data is amplified by interactions between datasets. The more datasets are released as open data, the more potential there is to link those datasets in new and innovative ways.

In her post Heather Savory uses the example of the flood data Environment Agency is planning to release next year (perhaps sooner). She suggests analysis of that flood data would be more productive if we also had more detailed open data from Ordnance Survey.

At the moment OS OpenData gives us postcode centroids (in Code-Point Open) that we could use with EA flood data. But what if we also had coordinates of individual addresses, or even building outlines?

Maximising Reuse of Open Data: An Illustration

It’s always difficult to anticipate all the ways in which open data might be reused. However I would like to expand on Heather’s example, drawing on my own experience using EA flood data and OS data together in a business context. Below is a (simplified) illustration of the difference that better OS data can make to the public understanding of flood risk.

The main flood dataset Environment Agency intends to release as open data is called Risk of Flooding from Rivers and Sea (RoFRS), although it was until recently better known as the National Flood Risk Assessment (NaFRA). This dataset is an output from modelling the EA uses to prioritise investment in flood defences. RoFRS is also the source of flood risk information used mostly widely in the UK insurance industry.

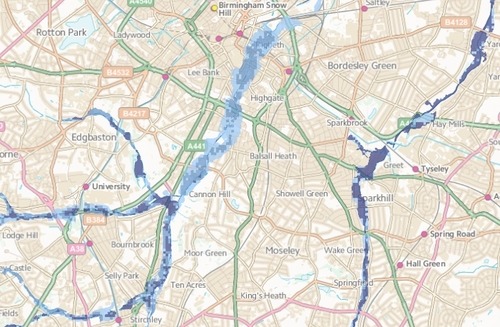

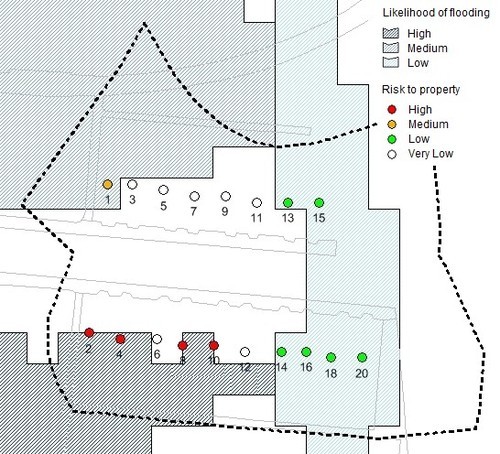

RoFRS describes the likelihood of flooding at any given location, using four categories of risk (High, Medium, Low and Very Low) averaged across a grid of 50m x 50m cells. At high level, on a map, RoFRS looks like this:

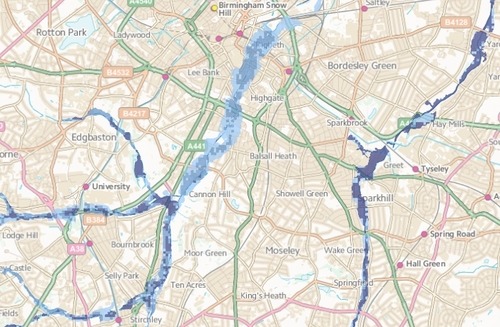

Drill down to the level of an individual postcode and the data looks like this:

As you can see the data is kind of blocky at this resolution. Like any flood risk model RoFRS is only “indicative”, particularly when laid over small areas of geography. (It’s generally difficult to produce a definitive view of flood risk at address level without a site survey.) But indicative is still useful for many purposes, and better than nothing even when thinking about the risk to individual properties.

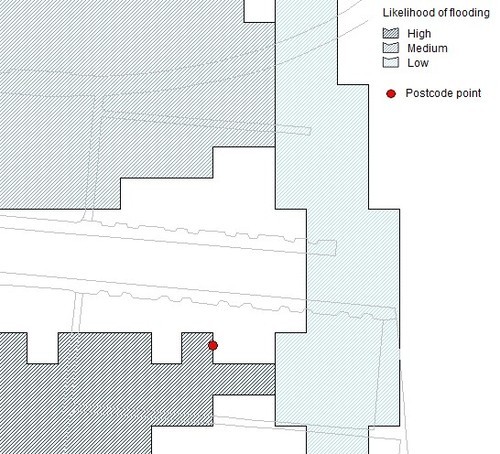

So how do we do that? The EA flood data gives us an idea of the relative likelihood of flooding for areas of land, but we need to geolocate our addresses (the flood risk “receptors”) as well. This is where the Ordnance Survey data comes in.

At the moment, if we rely only on OS OpenData, all we have is the postcode centroids available in Code-Point Open. In the example above that centroid is on the edge of a High likelihood grid cell. We know the addresses themselves are in the vicinity of that point, but not their precise coordinates.

So, to be prudent, we might assume all of the addresses in that postcode are at a High risk of flooding. (There are techniques we can use, such as buffering, to get a more nuanced view even without address points. But that takes additional expertise.)

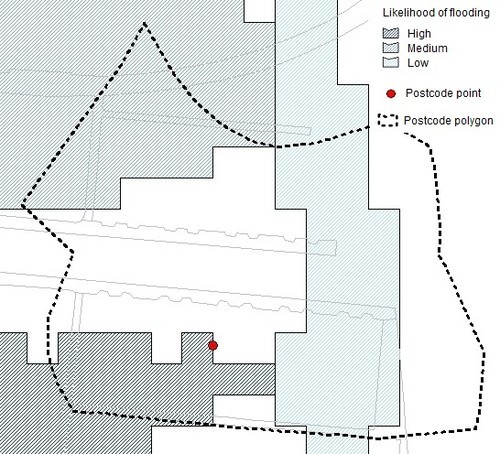

Here’s a better option:

If we had a polygon drawn around all of the address points in the postcode, as above, we could use GIS techniques to average the likelihood of flooding within that polygon. That would give us a better representation of the risk within the postcode, even without geolocating the individual addresses.

To do this we would need OS’s Code-Point with polygons product, which is not currently open data.

This isn’t a great approach anyway, because much of the space within the polygon is road rather than properties – and in a rural postcode properties might be few and far between. But it’s a better approach than relying only on the postcode centroid.

Or here’s an even better option:

Here we have the address points themselves. Ordnance Survey produces a number of geocoded address products, the most comprehensive of which is OS AddressBase Premium. None of those products are currently available as open data.

As you can see above, using the address points allows us to differentiate the indicative level of flood risk by individual address, rather than lumping the properties all together within the postcode. Of course we wouldn’t be confident of these results if buying a house, but for mechanical analysis of a large portfolio of properties this is a respectable approach.

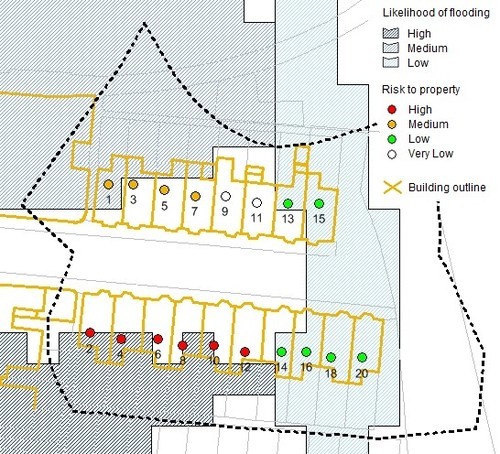

But … there’s an even better option:

Here we have building outlines, in addition to address points, for the individual properties. As you can see, in some instances the address point is outside the flood cell but part of the property is within the flood cell. That gives us a more detailed understand of the likelihood of flooding at each address. (Though bear in mind we are really pushing the resolution of the flood model here.)

We don’t have the building outlines as open data. They are included within the Topography Layer of OS MasterMap, Ordnance Survey most detailed and comprehensive mapping product.

Beyond Addresses - Other Contexts

In the above I’ve mentioned various Ordnance Survey data products that might be useful for analysing flood risk in a residential postcode. However OS publishes many other datasets, such as the OS MasterMap ITN Layer and the OS MasterMap Sites Layer, which would be similarly useful if analysing flood risk to transport infrastructure, commercial properties, etc. And risk to property is only one context in which OS data can amplify the utility of flood data; there are applications in reducing risk to life and promoting community resilience as well.

Disclaimer: The above is an illustration only. Proper analysis of flood risk, even in the jejune environment of the insurance industry, is a bit more complicated. If you’re a hydrologist please don’t make fun of me.

Image credits: The images in this post may contain Ordnance Survey data and/or Environment Agency data or derivations thereof. Or maybe I just drew all the lines with a ruler. Who knows? Derived data is confusing.