Post: 3 December 2013

At the end of October the Cabinet Office released a list of publicly owned datasets that have been nominated by government departments as “National Information Infrastructure” (NII).

You can download the list, along with the Cabinet Office’s narrative, from the GOV.UK site.

I have produced an annotated version of the NII list. I’ve sorted the entries by department, cleaned up a few typos in the dataset names, and added comments.

The original list includes, for most entries, a weblink to the relevant catalogue record on Data.gov.uk. I have provided additional links, usually either to a landing page for the dataset itself or to a page with more detailed information about the dataset.

I have also taken a view on whether each dataset is currently open, by applying the Open Definition.

What’s good about the NII list?

Most of this post is going to be criticisms, but let me start by highlighting a couple of good things about the NII list.

The fundamental idea is sound. Discovering public data assets is one of the main barriers to open data release in the UK. The Cabinet Office has approached that problem by requiring government departments to provide an inventory of their datasets, with the results uploaded to Data.gov.uk.

Since the start of October more than 5,000 previously uncatalogued items have appeared. The inventory is short on detail, and there are still many significant omissions, but this work is an important source of breadcrumbs for open data activists. Knowing a dataset exists is an essential prerequisite to securing its release.

Once we have a reasonably extensive list of data assets, the issue is sorting the wheat from the chaff. The Data.gov.uk platform is of little help in this regard; no amount of tinkering with the functionality can make up for a lack of information management. Drawing up a list of the most “important” datasets based on consultation and discussion is therefore the right approach.

Reading through the NII list in detail, I did find many entries that were sensible and unlikely to generate much disagreement. More importantly (for my purposes) the list brought to my attention several potentially valuable open datasets that I had overlooked.

A good example is the postcode-level Broadband Coverage dataset released by Ofcom in October. I discovered that on the NII list on Sunday afternoon, tweeted a link to it, and literally within hours @giacecco had turned the data into an online UK Broadband Coverage Checker. How cool is that?

So what’s wrong with the Cabinet Office’s NII list? Broadly there are two types of issue: weaknesses in the design of the project, and the poor quality of the responses from many Government departments.

Weaknesses in design

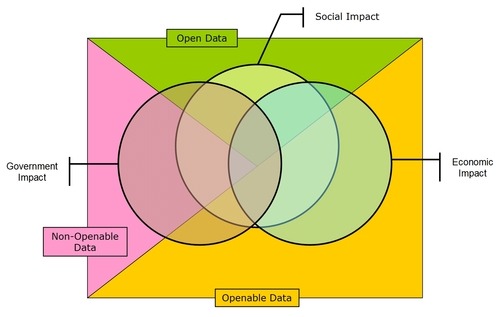

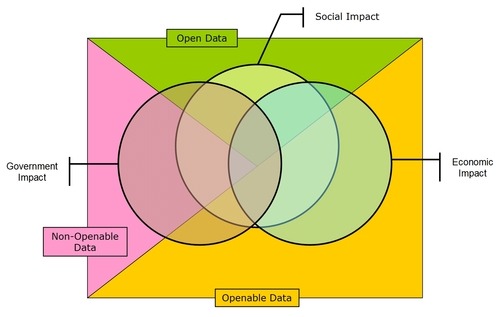

This diagram represents the ground that I think the Cabinet Office is trying to cover:

The central flaw is that departments were asked to assess their data assets based on potential to deliver economic growth, and/or social growth, and/or more effective public services, if they were made available openly.

There is no reasonable way to reconcile those criteria in a single list. How were departments supposed to weigh economic growth against social growth (whatever that is) as well as against the importance of the data to their own operations?

In practice the results mainly reflected departments’ own use of their data. In general there is no reason to suppose that departments have a clear understanding of how their data might delivery economic or social growth when released beyond their own operations; that would require an investment in market analysis.

More fundamentally, the potential for re-use of public data as open data is not a reliable guide to whether that data is “national information infrastructure”. While the utility of non-personal public data is almost always maximised by making it open, there are quite a few important datasets than cannot plausibly be released as open data.

By telling departments that the NII list would be used to prioritise datasets for open data release, the Cabinet Office encouraged them to discount data assets that they knew would never be plausible candidates for release (or that they were determined to resist releasing).

Essentially the Cabinet Office has tried to cover too many bases with this list. A better approach would be to draw up separate lists of datasets that are important to the economy, to society and to the operation of government and then, as a further exercise, identify which of those datasets (or their non-disclosive corollaries) could be released as open data with the most impact.

Quality of responses

The question of which public datasets are most “important” has wide potential for debate, particularly given the criteria given by the Cabinet Office. However, even with that latitude, the NII list is uneven. There seems to have been no real attempt to challenge departments on their submissions or to take an overview in order to identify gaps in coverage.

Of the 321 datasets on the NII list, over a hundred were statistical. This is despite the definition of dataset used in the Cabinet Office’s guidance, which specifically excluded official statistics. While statistics are often key information sources – small-area statistics such as the Census are particularly valuable – every set of statistics has one or more layers of more detailed data underlying it.

It is that underlying data that we should identify as the national information infrastructure. For the additional purpose of prioritising datasets for open data release, listing statistics in the NII doesn’t get us very far. All of the statistical datasets on the list are already open for re-use.

The NII list also includes at least eight entries that are simple duplications of other entries (and should have been weeded out in proofreading), as well as quite a few entries that are subsets of other entries.

Of the 197 unique non-statistical datasets on the NII list, 90 are currently open data and 107 are currently not open based on (my interpretation of) the Open Definition. However given the conflicting priorities in the design of the list I don’t think the proportion of open data tells us anything in particular.

All of this is just circling around the main problem: many departments have not produced plausible lists of their most important datasets, however far you stretch the definition.

The Department for Transport list is immaculate, and the lists from Health and Ordnance Survey are fine. DfE’s list is mostly fine except for the omission of EduBase. The Health list is pretty good but could be improved by drilling down below the statistics.

DCLG’s list is almost entirely statistics, and looks as if somebody just ran their eye down the catalogue on Data.gov.uk and picked a few that looked important. Although local government datasets were out of scope of the NII at this stage, there’s no obvious reason why DCLG should exclude major national datasets compiled from local sources (such as CORE).

Also missing: DCLG's Indices of Multiple Deprivation (IMD), which according to Data.gov.uk metrics is actually the public dataset of most interest to users.

The almost complete absence of significant environmental datasets is probably the greatest weakness in the content of the NII list. The Environment Agency has done more than any other public authority (excluding trading funds) to commercialise its data assets, and knows perfectly well which ones have the most economic potential. Where are the Flood Map and NaFRA datasets, where is the Detailed River Network, where is the LiDAR data, etc.?

However the EA is not quite the worst offender. Is it really conceivable that the Cabinet Office has 30 nationally important datasets, and the Department of Energy & Climate Change (DECC) has only one?

Significant omissions include: fuel poverty data, oil and gas licensing and field data, oil spill data, small-area electricity and gas estimates, and Ofgem's energy security indicators. It’s almost as if the Government thinks climate and the environment are just “green crap” …

I could go on. (Is Value Added Tax data really HMRC’s most important data asset? Why is the Valuation Office Agency missing completely?)

However, these are my main conclusions and recommendations: